From the Kids Table: Mind Your Manners

A writer recalls man-to-man dinners with his father at the fanciest French restaurant in his hometown, back when the reality of life hadn't felt so rude

Welcome to From The Kids Table, our personal essay series. On some Sundays, we’ll ask writers to share childhood memories about dining out. For our fourth installment, writer and humorist John DeVore recalls getting fancy French meals with his late father and how he misses the decorum those days and dinners demanded. We hope you enjoy, and would love to hear your feedback in the comments below.

Licking your fingers at the table is impolite, but I was busy inhaling chicken tenders at a diner. I sat beside a mother and her daughter, who served me side-eyed. I know better, yet I was sucking honey mustard off my thumb.

I think I may have forgotten how to behave in society. I slurp my soup. I stab dumplings with chopsticks. I tip appropriately, but I also steal individual cracker packets. I stuff them in my pockets like they're a form of currency. I still cover my nose when I sneeze, but I've become a toothpick person, just picking my teeth willy-nilly.

I've changed, and I don't know when that change happened precisely.

I recently watched a bearded middle-aged man sit on a park bench and eat a burrito side to side like a giant corn on the cob. He didn't even wipe the sour cream and beans out of his beard when he finished. He just sat there and stared at the sun. I'm ashamed to admit it, but I related to that guy. Is society spinning out of control? Am I?

I haven't always been so uncivilized. I know the basic rules of etiquette because I was taught them. For instance, there are some restaurants where you should wear your finest clothes, but I haven't worn a tie in years, and the last time I did was at a funeral a decade or so ago. I followed the standard protocol of the funeral buffet, though, and did not heap piles of mayonnaise-based pasta salads on my plate—just one modest scoop per serving.

My brother visited me in New York from Texas last year. He had made a reservation at a Michelin-starred restaurant, which was on his bucket list. I was not at my best. When the maître d' pulled out my chair, I flinched. I wore a hoodie, and hunched over the amuse-bouche like a goblin. Afterward, he asked how I was doing on the train back uptown, and I shrugged. What I didn't say was, "I miss dad."

There was a time when I was a little gentleman. I minded my manners. I sat up straight. I never slurped, burped, or talked with my mouth full. My pants were not napkins. I was ten years old, and life made sense.

I used to dread these dates because I'd have to put on slacks, wear uncomfortable dress shoes, and comb my hair, but my mood would change once the maître d' guided us to our table like we were the most important people in the world.

The fanciest restaurant in the history of the world was an intimate French establishment tucked away in a Northern Virginia shopping center. Its name was La Mirabelle, and it closed in 1997 after 20 years of serving patrons exactly what you'd expect to be served at a French restaurant far from Paris: coq au vin, calves liver, steak frites.

In the late 80s, my idea of cutting-edge cuisine was Lunchables, the mass-produced lunch box filled with stacks of processed meats and cheeses.

La Mirabelle took itself seriously. The restaurant didn't have to enforce a dress code because every man knew to wear a jacket, and every woman a dress. The dining room had white tablecloths, crystal goblets, and servers wearing tight black vests. It was a palace of propriety.

One of the two owners was the maître d', my first. I don't think he wore a cartoonish French mustache with upward twists at each end, but that's how I like to remember him. He was brusk and efficient and always pleased to learn you had made a reservation. My dad always made a reservation because he understood that there are rules in this life that must be followed or everything falls apart.

He was a big believer in not saying anything if you can't say something nice. I blame his Baptist upbringing. "Do unto others," etcetera. If I popped something in my mouth that did not agree with me, I was instructed to choke it down and then smile politely. The answer to "Would you like some more" of that offending food would be a firm "No, thank you." But fresh pepper? Or more cheese? Yes, please.

When in doubt, say "please" and "thank you," the two pillars of politeness. I know that seems quaint, but that is because we live in rude times.

When I was growing up, there were three primary eating establishments where my family would eat. First, there was fast food, which we'd eat when my dad had to work late, or my mom was too tired to make dinner. McDonald's was our go-to, and a Fliet-o-Fish and chocolate milkshake was what I'd get—an excellent pairing.

Next came church food, the casual, family-friendly eateries we'd visit after Sunday services. This meant we were dressed up, and I'd get to sit down to a stack of pancakes or a grilled cheese sandwich. And then there was special occasion food, pricey restaurants where we'd celebrate birthdays, certain holidays, or just good news. The family favorite was an upscale Greek bistro that served flaming cheese. But then there was La Mirabelle, reserved for my parent's anniversary and semi-annual 'father-son' dinners where the future would be discussed.

Specifically, my dad would ask me what I wanted to be when I grew up, and I'd dream big: astronaut, president, bounty hunter. We would debate the merits of each profession over drinks, him sipping a sophisticated gin and tonic while I nursed a Shirley Temple. When I ate quickly, he'd remind me to eat slowly, chew my food, and enjoy the flavors. He spoke calmly, like a wise Kung-Fu master. One should refrain from filling up on bread. I remember that directive, which I still struggle with, especially at restaurants that offer never-ending breadsticks.

At these dinners, I learned how to conduct myself in public. First, and most importantly, one was supposed to make eye contact with your server and your dinner mate. It's a sign of respect. Then, the napkin goes in the lap, followed by a thoughtful study of the menu. One should ask if there are specials. One should then be decisive and order with confidence. One should not second-guess oneself. One does not wave their utensils or hands in the air. One controls oneself.

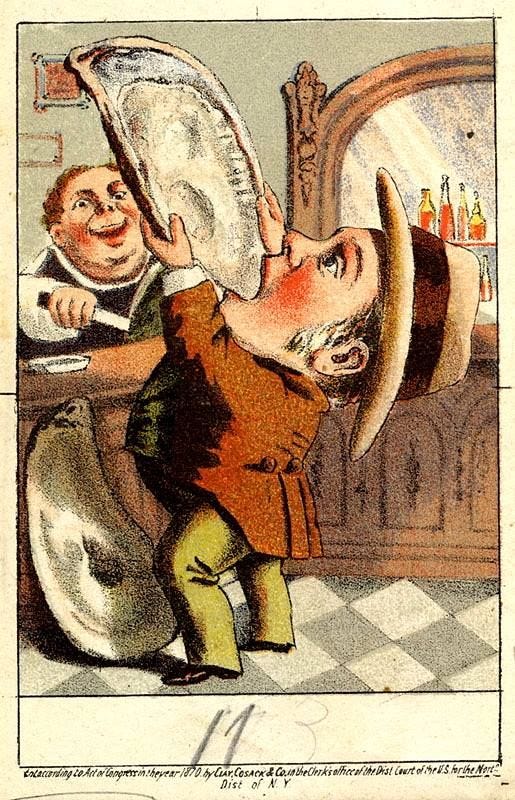

My lifelong love affair with oysters began at La Mirabelle, even though the first bivalve I ever swallowed shocked me with its briny viscosity. I believe I called them "mermaid boogers."

At La Mirabelle, I first expanded my culinary horizons and experimented. I was allowed to order whatever I wanted, but I had to eat it. My lifelong love affair with oysters began at La Mirabelle, even though the first bivalve I ever swallowed shocked me with its briny viscosity. I believe I called them "mermaid boogers." I did not like sweetbreads, and I still don't. My dad swore by La Mirabelle's preparation and always ordered a plate of their perfectly seared thymus glands.

I could never work up the courage to eat beef tartare, so I avoided it even though my dad encouraged me to try it, but he did convince me to try escargot. The idea that I was eating snails intrigued me, and once I realized the dish is meaty blobs drenched in garlic butter, it became one of my favorite foods, a sort of party trick. "Who wants to watch John eat snails?"

I was a messy kid whose parents tolerated a certain level of disorder. They knew I was the type of kid more likely to melt the faces of his action figures with stolen cigarette lighters than build complicated LEGO sets. In the vocabulary of the time, I was hyperactive, and my folks loved me anyway. They loved me because I was who I was. They accepted that I was a human blender, always buzzing.

But my dad did not tolerate such antics in a pew or at the dinner table. And La Mirabelle was the top rung of the McLean, Virginia social ladder, and a night out there was a true test of one's modesty and decorum, virtues that separated good boys from animals. My dad was strict, but these "man-to-man" evenings were fun. He listened to me, asked me questions, and believed that adults should know when to say "excuse me" in public (when leaving a table or after accidentally producing rude noises.)

Eventually, when it became my brother's turn to talk about the future, man-to-man, my dad changed tactics: they slid into the booths at the local Pizza Hut instead and ordered a large with sausage, mushroom and mushroom, and extra cheese.

I believe, and this is my theory, that my dad's original idea was that meaningful conversations should happen in a prominent place, and La Mirabelle fit that definition. On a Friday night, the place was packed with suburban professionals quaffing glasses of Merlot and praising the duck confit, and popping sticky profiteroles into their mouths, all while servers zipped to and fro. The chandeliers twinkled, and the glasses clinked, and there was the constant hum of people having meaningful conversations while stabbing their salade niçoises with chilled salad forks.

As a teenager, I heard rumors that La Mirabelle's small-ish bar was where lonely divorcees and swingers would meet and hook up, but I never dared to visit with my fake ID.

In retrospect, La Mirabelle's service and food were earnest but mediocre, at least by today's standards. There was no way it could have been exceptional. There was no fine dining competition in my sleepy town, except for the Greek bistro, but that place's ambitions were simple, more down-to-earth. It didn't help that La Mirabelle was a quick twenty-minute drive from Washington DC, a city famous for its boring food scene (unless you're talking Ethiopian food.)

This is just how it was. The 80s are remembered as colorful, patriotic years but also deeply insecure. The nation was prosperous and fabulous for some, yet I'd lay in bed at night listening to my parents work out how to pay that month's bills. McLean had its fair share of wealthy and powerful politicos, but modestly salaried bureaucrats and congressional staffers mostly populated it. La Mirabelle was a beloved, friendly, nearby restaurant to go to when you got that promotion. It aspired to more, but it was enough.

I had dinner at La Mirabelle just a few times, maybe four before high school, and my dad's increasingly stressful job changed the comfortable rhythms of my childhood. The last time we went, I showed off my skill with the escargot tongs. I used to dread these dates because I'd have to put on slacks, wear uncomfortable dress shoes, and comb my hair, but my mood would change once the maître d' guided us to our table like we were the most important people in the world. I dimly remember enjoying the ceremony. It made sense: put on church clothes, order a crepe, and laugh at my dad's jokes. It was comforting. Civilized. I felt secure at La Mirabelle, the world's fanciest restaurant. But that was last century. A very long time ago.

Such a great read -- one we're thrilled to publish. For more from John DeVore, check out his ode to Taco Bell and what it was like growing up biracing in America: https://www.eater.com/2014/11/5/7155501/life-in-chains-kfc-taco-bell

Fantastic, intelligent, and very funny essay!