From The Kids’ Table: Ode to the On-Mountain Meal

A writer reflects on the many meals he’s had slope side, and why lunch—even a cafeteria pizza—always tastes better following a morning of skiing

Everyone carries a whiff of their hometown, no matter how much distance they try to put between themselves and the place. As for me, I grew up as a townie—a resort rat—in a New Hampshire ski town, where my Austrian father ran the local ski school (back then, Austrians ran ski schools in America the way gourmet restaurants always had a French chef in the kitchen). This makes me a skier, through and through, despite my best efforts to shake such a one-dimensional persona. Skiing is the first (and sometimes only) thing people ask me about, though I suppose I’m also to blame. I still get excited when the leaves fall in November and depressed when the first buds return come April, right here in New York City. I still pine for pine trees laden with snow, love the municipal mayhem of an old fashioned Nor’Easter, and when a frigid wind whips through the city and folks complain, I need to restrain my inner cold weather lover (which, appropriately, manifests as a grouch) from telling them to “go move someplace warmer, then.” Humbug, indeed.

But perhaps what I love best about skiing—even more than first tracks, and deep powder, and bluebird days, and whatever other indelible attributes we associate with the sport—is the food, from the overpriced garbage I shovel down in a cafeteria to the good stuff you find in fancier resort towns. Ditto goes for drinking. There’s just something to be said about indulging in the comforts of a good hot meal and/or a warm buzz in a cold place, and I’d argue that there’s no finer place to do so than on the side of a mountain. I have friends who are perhaps purer skiers than me, meaning they’re the type of people who would prefer to scarf down a pre-packed sandwich on the chairlift rather than sacrifice a few runs by stopping for lunch. To me, this is crazy.

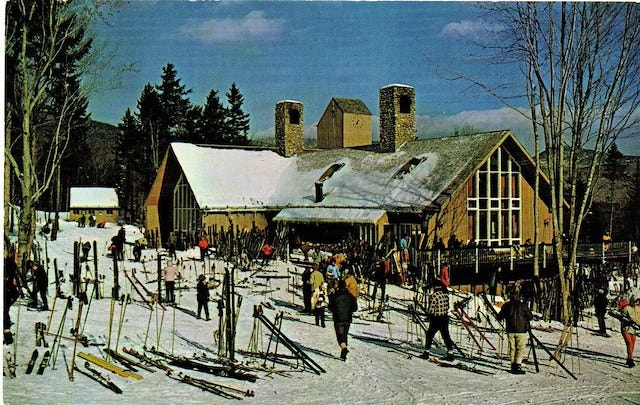

My love affair with lodge food began early. Having a father who worked all winter long running the ski school seven days a week, the mountain—a little place called Waterville Valley, funded by the Kennedys and notched in New Hampshire’s White Mountains—became my de facto babysitter. This was especially true on winter weekends, when I, a shy kid in all other walks of life, resumed my role cosplaying as one of the rich brats in the seasonal ski programs, and later on the race team. When I wasn’t pissing off the ski patrol by skiing too fast down the mountain, I swaggered around the lodge in my unbuckled ski boots, pilfered cafeteria trays and used them as sleds, and spent a good deal of time in the ski instructors lounge. Of the latter, I can still smell the sour smell of beer wafting from kegs and the sharp, chemical tang of hot ski wax being ironed into the bases of skis.

I also spent a considerable amount of time looking for my father, who, being a bit of a showboater, and a man allergic to paperwork, was seldom found in his office. What I always needed from him was lunch money, something he was loathe to give me given the cost of everything, even with his employee discount, which the old ladies working the cash registers extended to me. Where I wanted to spend Dad’s lunch money was at the pizzeria on the second floor of the base lodge. It stood wedged in a corner, below the staircase that led to the third floor après bar, and to the left of the cafeteria, where the burgers were the greasiest I can remember. Sometimes the line for pizza spread all the way from the front counter of the pizzeria to the lodge’s freestanding fireplace, halfway across the second floor, its four-sided hearth flanked by skiers removing their boots to thaw their feet out over lunch as they talked lighthearted shit in their heavy Boston accents. To me, the pizzeria’s long line was warranted, as was the precarious act of trying to balance two slices of cheese pizza and a fountain coke on a tray while clomping down the stairs in my ski boots back to my father’s office (a journey that still fills me with fear). I would eat lunch at his desk, streaking tomato sauce on his papers and whatever else I rifled through while eating. The pizza served in the Waterville Valley base lodge was, and remains in my mind, even though I cannot recall its exact taste, the finest pizza I have ever had in my life. The tomato sauce, the puffiness of the crust, the exorbitant amount of cheese — all of it. I am sure were I to have it now it would disappoint, monumentally so, as most things from one’s past do, but since I cannot, it will forever remain cemented in my mind as the platonic ideal of pizza — a totem that takes me home.

Over the years, I’ve enjoyed ostensibly better meals in better ski resorts. It began in Utah, Deer Valley to be exact, where I joined family friends and first—if you can believe it—had oysters, some 30 or 40 of them by the time the night was through, much to the amusement of the adults, who all made jokes (none of which I grasped) about my sure to be surging teenage libido. In my 20s, I discovered Austrian après-ski on the side of a mountain high above St. Anton. There, at the Krazy Kanguruh and The Mooserwirt, the two bars that serve as a one-two punch at the end of everyone’s ski day, I learned the fine art of table dancing in my ski boots while swilling steins of Austrian beer and downing Jägerbombs. Put these two bars anywhere else in the world, and they are the epitome of tacky; but slap them on the side of a mountain, and this snob is in his happy place.

A year later, I found myself in St. Moritz for the season, the place where my parents had met, and working as a ski instructor, just as my father once had. This meant that in addition to teaching my clients how to turn, as well as schlepping their gear from the lobby of The Palace Hotel to the lift, I was in charge of lunch reservations. The slopes of St Moritz—Corviglia, that is, the main resort—are lousy with lunch spots. Alpina, Trutz, Chadafö, Paradiso, the latter rife these days with influencers. But the real spot, back in those days, was La Marmite, cantilevered over the slope like a ship cresting a white wave. Floor to ceiling windows gave way to the Engadine Valley, far below—a valley that Nietzsche once claimed had saved his life—but the guests were always too preoccupied with their food and the scene to care. I must’ve taken clients there some 50+ times that season. So much so that the ski school director, a man who called himself “The Robert Redford of the Alps,” admonished me for fleecing too many guests out of a free lunch. But, hey, I had a thing for the place’s truffled flammkuchen (a wafer thin pizza that went for $100 a pie) and their venison, served with a fried egg over polenta and gruyere. One time a client ordered a magnum of Riesling and insisted on skiing home. It took us over two hours to get down the mountain that day, and she fell so many times that she’d ripped the seat of her Bogner one-piece to shreds.

There were other clients in St. Moritz, of course, many of them better behaved. Surprisingly enough, the Trumps rank among them. Ivanka and Don Jr., upon learning that I would have to adhere to the Downton Abbey-type rules in the private Corviglia Club and eat downstairs with the rest of the instructors (aka “the help”), cancelled their reservation and opted for the cafeteria instead, so that we could all lunch together. I remember laughing over fries and thinking how normal they were. And then there were the ski instructors, the more senior and charismatic of which called the shots. On a particularly miserable day in February, St. Moritz and the rest of the Engadine socked-in with a low-elevation white out and pummeled by an icy snowfall, I was paired with a fellow by the name of J.P. He had a permeant sun tan, his skin as leathery as a catcher’s mitt thanks to not having experienced summer in three decades (he taught in Australia during their winter), and—despite being in his fifties—skied like a badass, usually with a Gauloises cigarette wedged between his chapped lips. J.P. had taken a shine to me earlier that season, mostly because he knew that my father had been an instructor in St. Moritz back in the ‘70s, and he taught me things, like how only rubes believed you couldn’t drink red wine with fish, and that if you wanted to stay at the bar past 7 p.m., when all instructors were expected to return home and change out of their uniform lest they incur a 400 CHF fine, all you had to do was turn your red jacket inside out so that it looked like a generic black parka.

“Putain” JP spat on that cloudy day, looking at me and shaking his head at the exuberance of our clients — a corporate group from Deutsche Bank.

JP devised a plan that would lead to minimal skiing. Where to stop for coffee, a long easy run to a neighboring town followed by an even longer gondola ride sure to eat up plenty of time, and when to break for lunch. When the wine list arrived, JP grabbed it, rolling his eyes at the client who’d dared try to snatch it first. JP only ordered the good stuff, and plenty of it. He got our clients so drunk that afternoon that they all downloaded on the funicular back to town and called it a day.

On the last day of that ski season in St. Moritz, Bar Finale, down in Celerina, gave away all its remaining alcohol for free to instructors (the only people left in town), and I promised myself that once I’d drank enough I’d finally say hi to the blond Swiss girl I’d been making eyes with all season. Sadly, the place ran out of booze long before I’d summoned enough liquid courage to approach her.

My skiing, and thus my mountain lunches, have decreased since then. Still, there have been a few good ones. Hot dogs and cans of Fat Tire at the Dawg Haus at the base of Blue Sky Basin on the backside of Vail. Or ducking the rope off Game Creek Bowl and skiing down to Minturn for Mexican and margaritas at the Minturn Saloon, where old school skiing paraphernalia festoons the walls and the pitchers go down so smooth that you always miss the bus and need to call a cab home. At the Hospiz Alm in St. Christoph, Austria, there’s a slide to the bathroom in the basement to save guests the trouble of having to take the stairs in ski boots after lunch, and on the sun terrace at the Alter Goldener Berg in Oberlech, you can’t go wrong with a lunch of speck, kaspressknödel, and kaiserschmarr’n — though, and I speak from experience here, it might cut your ski day short; consider yourself warned. If you ever find yourself in Kitzbühel, particularly during Hahnenkamm weekend, try to scare up a Salzburg-style “bosna” from one of the street carts (and tell them to go hard on the curry powder). And here’s a deeper thought: an on-mountain restaurant just might save your life, as it did mine. It was some six years ago, atop the Passo Pordoi in the Italian Dolomites, at the Rifugio Maria, over Neopolitan-style pizza and spritzes with my wife, that I first began to come to terms with my father’s death. While looking out the window at the glacially capped Marmolada, a mountain Dad had long mythologized, I began to see him not as the seemingly indomitable six-foot-four man who had somehow irrevocably succumbed to cancer, but as a myth in his own right, whose spirit was now draped upon this alpine land he once called home, or anywhere—really—that I was fortunate to traverse on a pair of skis.

Since having kids (two boys, the eldest of whom we named J.P., after my instructor pal), my ski territory has contracted, and my big trips have all but gone away. We go up to Vermont frequently to see my mom and to sneak in a little skiing, and sometimes up to New Hampshire, too. But I’ve spent a good deal of time at miniature mountains teaching my children. One isn’t even a mountain, but an artificial slope at the American Dream Mall in East Rutherford, NJ. It is there, indoors on artificial snow, the temperature tuned to an unwavering 28 degrees Fahrenheit, and never the slightest gust of wind to spoil things, that I’ve taught both boys the basic fundamentals of the sport. Our classroom is a far cry from Dad’s Alps, or even Waterville Valley; still, as sacrilegious as it feels, it gets the job done, and we always make sure that we reward ourselves with lunch afterward. While there is no lodge to speak of, there is a food court in the mall, and sitting there in our snow pants, our skis propped up beside us, our jackets piled on a chair, it almost feels as if we’re somewhere high up on a mountain. We get slices of pizza from Best Pizza. It’s far better than the pizza I bought with Dad’s money all those decades ago in the base lodge at Waterville Valley, surely, and yet sitting there, the three of us silently chewing our slices, replenishing ourselves on dough and cheese and tomato sauce, it somehow reminds me of it. Maybe it’s the fact that we’ve earned this food, and to know that I have passed this sport down to my children, all of it, lunch included. Or maybe the pizza itself is a time machine, and eating it after a morning of skiing makes me feel like a kid again.

I hope that someday my boys will explore the ski world as I have, and that whatever they eat on the mountain—the lodge dark compared to the sun-splashed slopes, the two of them feeling momentarily blind as their eyes adjust to the interior—reminds them of splitting a pizza with Dad at the mall after skiing, back long ago when they first learned the sport.

At the Central New York mountain I practically grew up on it was the donuts, the hot chocolate, and the goulash, each with a smell those foods will never have again for me. The goulash was just mini-shells covered in chunky canned tomatoes, baked in a giant hotel pan, and stuffed into styrofoam cups for serving. It was like a pound of pasta slop in a 12oz cup but so good.

Always pack a handful of sandwiches in my trail bag to dip a rope somewhere and enjoy a cold beer and a turkey Sammy in the woods.