From the Kids Table: The Proustian Power of Restaurants

Whether staving off the week ahead or unlocking the past, sometimes a restaurant can function with all the magic of a time machine

Welcome to From The Kids Table, a new, personal essay series we’re beta testing. On some Sundays we’ll ask writers to share childhood memories about dining out. First up is our very own James Jung, who recollects winters in New Hampshire and what dinners out in a tourist resort felt like as a townie. We hope you enjoy, and would love to hear your feedback in the comments below.

Last Sunday, I met my in-laws for dinner at a red sauce joint in the east sixties of Manhattan. My wife and two young boys — ages five and two, respectively — were already there, while I, as usual, was running late. I won’t name the restaurant because it’s one of those dated and gaudy places that can easily be maligned for its questionable decor and basic takes on Italian-American food. There’s a touch too much sugar in the tomato sauce, and the kitchen staff’s liberal use of the deep fryer is excessive. On the bright side, the baked ziti bangs. The zucchini fritti pop into your mouth as addictively and crisply as Pringles. A bottle and a half of chianti and the two-acre square of tiramisu? Mama Mia! As a friend who grew up in the neighborhood told me with a commiserating smile and a shrug when citing the place’s ample portions — a friend, I’ll add, in possession of a palate far more discerning than my own — “at least you won’t go home hungry.”

Still, as I trudged southeastward to meet my family, I didn’t anticipate our meal with much enthusiasm. In-law jokes aside, it was the destination that depressed me. As parents, nights out are rare for my wife and me these days, and to use one on such an unremarkable restaurant felt like a waste. My oldest son was to blame for the choice. Five days a week we pass the restaurant on our walk to his grade school, and it’s precisely the place’s loudmouth facade — the scripted sign, as big and subtle as a billboard; the multiple brick archways, each one in my mind evoking a pizza oven; the bright red awnings, wagging in the brisk winter wind like wolfish tongues — that to my son screams class and sophistication; an elegant eatery worthy of his patronage, as if tailor made for a big night out on the town. And so, of course, my wife, her parents, and I all acquiesced.

My wife and I can be food snobs, vibe snobs, downtown dilettantes who’ve surrendered to uptown ease, but we’re not monsters. If our kids are demanding a night on the town — with us! — then bring on the bolognese.

Growing up, dining at a restaurant on Sunday nights was tradition in our family of three, especially in winter. We lived in a backwater ski resort in New Hampshire’s White Mountains. Our town stood at the terminus of a ten mile road that wound through the wilderness and was encircled by a jagged rim of four thousand foot peaks. To my Austrian father, who’d relocated us there after he was hired to run the resort’s ski school, these mountains amounted to no more than hills. To my Brooklyn-born mother, the mountains felt isolating — a barrier between us and the rest of the world, which announced itself in the form of a hum drum state college town some 30-minutes down the river. We went there once a week to go grocery shopping. No one felt more out of place, however, than me. I was a shy and introverted kid in the classroom, and my ungainliness and sensitivity did me no favors at recess.

Winter weekends were different. I could ski fast, and this made me popular in a racing program filled with brash boys whose wealthy families arrived every Friday night at the condos and stately second homes that stood otherwise vacant during the three other seasons of the year. Among these kids, I felt worldly, cavalier, and sometimes I could dish it out on the slopes just as badly as I got it on the school yard. In short, I was a vastly different boy on winter weekends. But, on Sunday nights, when the town cleared out and contracted back to its 250 full-time residents, when the moonlight glazed the snow between the trees at the back of our house and you could hear the coyotes howling off in the hills, when the prospect of all the ragging I’d surely endure at school throughout the week ahead began to hang in the air, the blues set in.

My parents must have felt these blues too, because — more times than not — my mother would pipe up with her usual suggestion:

“Oh let’s go out to dinner,” she’d say, always as if the thought had just come to her. My father would play his role too, hemming and hawing about money while wringing his thick farmer’s hands, complaining about exhaustion — the lessons he’d taught, the torch light parades he’d led, the skischule abends he’d hosted — yet always in the end surrendering to the whims of his wife. And then there was me, their only child, their perpetual sidekick, excited by the idea of staving off reality, if only for the course of a meal. Living in a tourist town, we served the tourists — even me, the shy townie who transformed into a wise-cracking ski racer nearly capable of tricking himself into thinking he was a rich kid on the slopes. But, on Sunday nights it was our turn to be pampered a little.

Plus, on Sunday nights our town’s handful of restaurants would be empty and that meant the whole place was ours, which lifted everyone’s spirits. My prematurely silver haired father, a natural skier and showman, something of a small-town celebrity, no longer had any over-enthusiastic tourists demanding his attention — free pointers under the lift, yodels for the kids on-demand — and ensuring he’d come home in a foul mood. At a restaurant on a Sunday night, Dad was just Dad. He was warm and hospitable, forever a figure and a focal point in our family, however antiquated and patriarchal that might sound now.

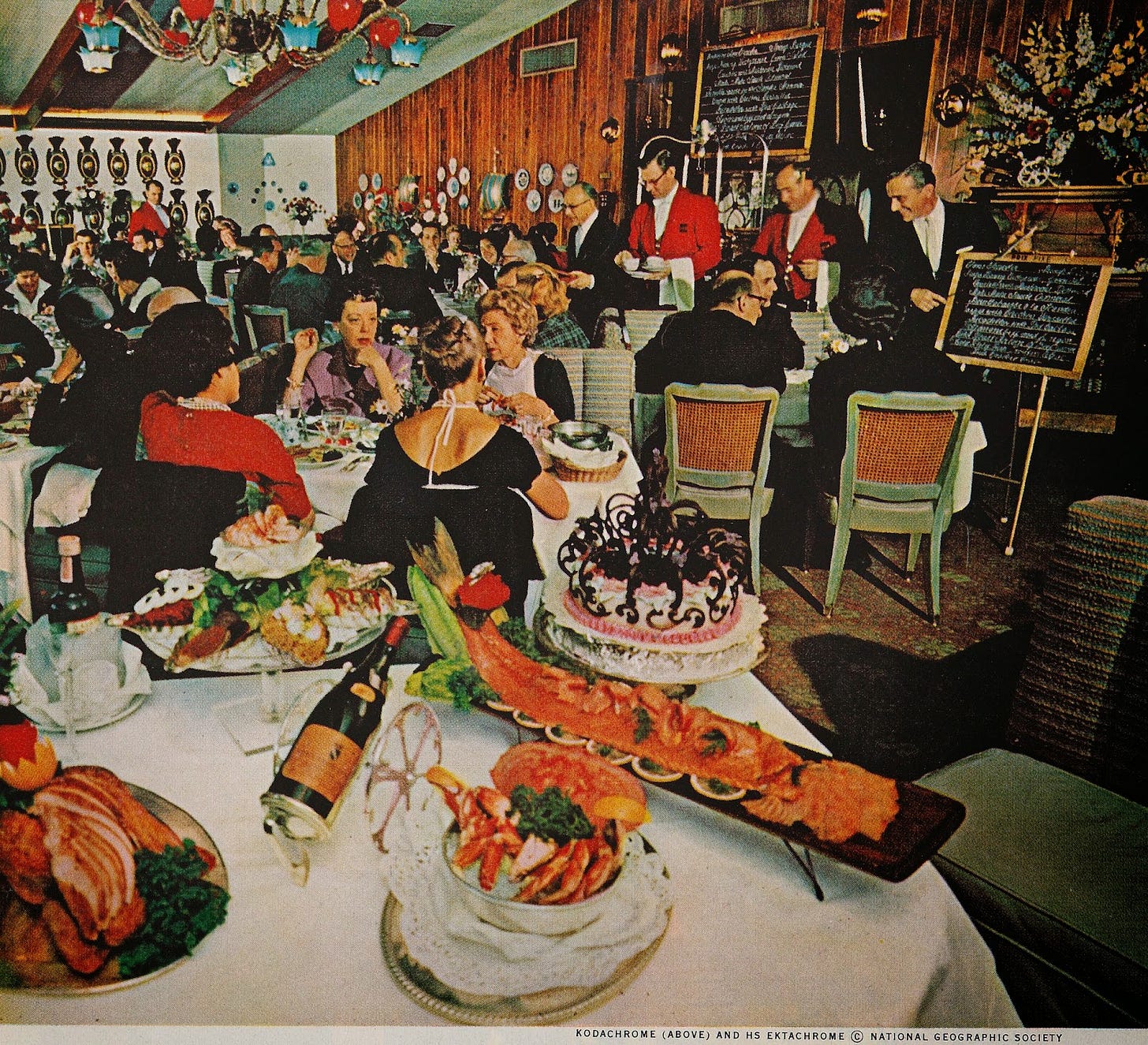

Mom, for her part, transformed back into the glamorous woman she’d once been before I was born, when a modeling career had brought her all the way to Paris, France, a city I’d only read about in books. “I just like going out sometimes,” she’d explain to me. “It doesn’t have to be fancy. You don’t have to cook. You get to dress up a little.” On went the makeup, the jewelry, and maybe even a fur from her ex husband. (Her ex a man my father might soon forget had he not found the look of his wife in such frocks so fetching.) I think my mother loved these nights best. Here was a woman who’d grown accustomed, among other things, to the best restaurants, and she’d given it all up for my father and for a lonely life in the sticks.

Of the ones we frequented, I remember two restaurants best: one Swiss, the other Mexican. At the Swiss restaurant we sat at a small table wedged into the corner of the nearly empty bar. Mom and Dad jokingly referred to the table as our stammtisch. My father would have a tall weisse beer — his only beer of the week — while my mother sipped Chardonnay, and I would guzzle down one Coke after the next, prosaic concerns about caffeine overdoses and being up all night belonging to the real world, not the magical, time-stands-still world of a restaurant. The fondue we always split would taste sharply of kirschwasser — I can still taste it — compliments of the cook, a good friend of my father’s. We’d eat the meal down to its dregs, scraping the burnt, blue-black cheese bruising the bottom of the pot, my father all the while instructing my mother and me how to do so and reminding us with the conspiratorial air of a connoisseur that this was secretly the best part.

The Mexican restaurant offered a more low-key affair, but a no less cherished one. My father wouldn’t be as deft with his fajitas as he was with fondue, my mother would prefer her margarita over the enchiladas she ordered, and there I’d be making quick work of my hamburger and fries, paired of course with a Coke. The couple who owned the place were transplants from Key West. They’d made some money down there as part of a diving crew that had discovered a trio of sunken, treasure-laden Spanish galleons, and this of course added to their fish-out-of-water lore. Whenever they came out of the kitchen and into the desolate dining room they would appear stunned, as if they’d only just realized they’d swapped the good life of the Florida Keys for the hardscrabble winters of northern New Hampshire. I was too naive back then to realize that the couple’s stunned demeanor had more to do with the fact that they were always half in the bag. Had I known so I doubt such knowledge would have diminished them in my eyes. Like all good restaurant folk, these were outlaws, characters, soldiers of fortune who’d chosen the path less traveled and all that jazz.

I mention this ancient history because these memories hit me squarely last Sunday night when I walked downstairs into the aforementioned red sauce joint’s subterranean dining room. Suddenly, I wasn’t the savvy, big city person it sometimes seems like I’m pretending to be, the one who’s made a career in media and now, at least tangentially, tech. Instead, I was still the kid from New Hampshire, the one not yet jaded enough to dismiss a Sunday night dinner at a less-than-hip restaurant. I told the hostess that I was meeting my family, and as I rounded the corner I saw them sitting there, halfway back in the brightly-lit room. My in-laws sat on one side of the table. I’d have preferred my own parents, but Mom now lives alone up in Vermont and Dad died three years ago. In fact, it was at this same restaurant that the three of us had dined together while Dad was receiving treatment at Memorial Sloan Kettering. Not the best memory, but not the worst either, and probably one that explains why I have a soft spot I can’t quite pin down for this place. My wife sat on the other side of the table and saw me and smiled. We’ve had our problems like many couples, but on this night she was happy to see me, and I her. And then my kids spotted me, the two boys. They sprung up in their seats, their eyes wide. They cheered and chanted my name, much like I would have done for my own father. They beckoned me closer with great pomp and magnanimity, like two princes welcoming a guest into their domicile where an impressive feast was due to commence. “Esset mir hobn,” I could hear my father saying in the bastardized German dialect that was the preferred tongue of his tiny Tirolean town. “Eat, we have everything.” It’s what he’d say whenever we had guests for dinner, and then laugh and laugh at the resulting confusion. I could see my mother rolling her eyes at the heavy-handed joke she’d heard far too many times. I imagined her wishing now, just as I was, that we could hear him say it one more time.

And so I sat down. I smiled at everyone. My five year old got out of his seat and rounded the table to give me a hug, babbling this and that, aquiver with excitement. He often suffers from the same shyness that afflicted me as a kid, which makes me worry sometimes, especially on our walks to school. Thus, whenever I see him break out of his shell I’m happy. I looked around the room as he retook his seat. I looked at the other parties, saw the strangers, imagined their stories. I watched the waitstaff moving as if the place had an in-house choreographer, my pre-judgements about the restaurant now feeling capricious and silly. The tacky decor of the place seemed to fall away. So too, I hope, did my snobbery. It was Sunday night at a restaurant, and that was good enough for me.

James Jung

VP, Content

Blackbird Labs, Inc.

Thanks for reading! Blackbird will launch in select restaurants later this year. In the meantime, if you dug this, please give it a like! We’re also on Twitter and would love to hear from you there.

Lovely piece.