From the Kids Table: Divorce Sushi

Could suburban sushi dinners between a divorced dad and his daughter mend their strained relationship?

Welcome to From The Kids Table, a personal essay series we’re beta testing. On some Sundays, we’ll ask writers to share childhood memories about dining out. For our third installment, author Katy Kelleher writes about her parents’ divorce, and how she and her father attempted to mend their strained relationship through the power of raw fish. We hope you enjoy, and would love to hear your feedback in the comments below.

There’s a trope in rom-coms where the two leads bond over people watching. Maybe they’re at a bar, scanning the room and making comments on how long various couples have been together. Maybe they’re sitting on a park bench, making up stories about the people who pass. This game is adorable and twee when it happens on screen—oh how sweet, the elderly couple holding hands! Oh how nice, the divorcee on her first good date in years! In real life though, eavesdropping is rarely so pleasant. Keep your eyes on your own charming companion, lest you witness a truly sour scene, a dinner like so many of mine.

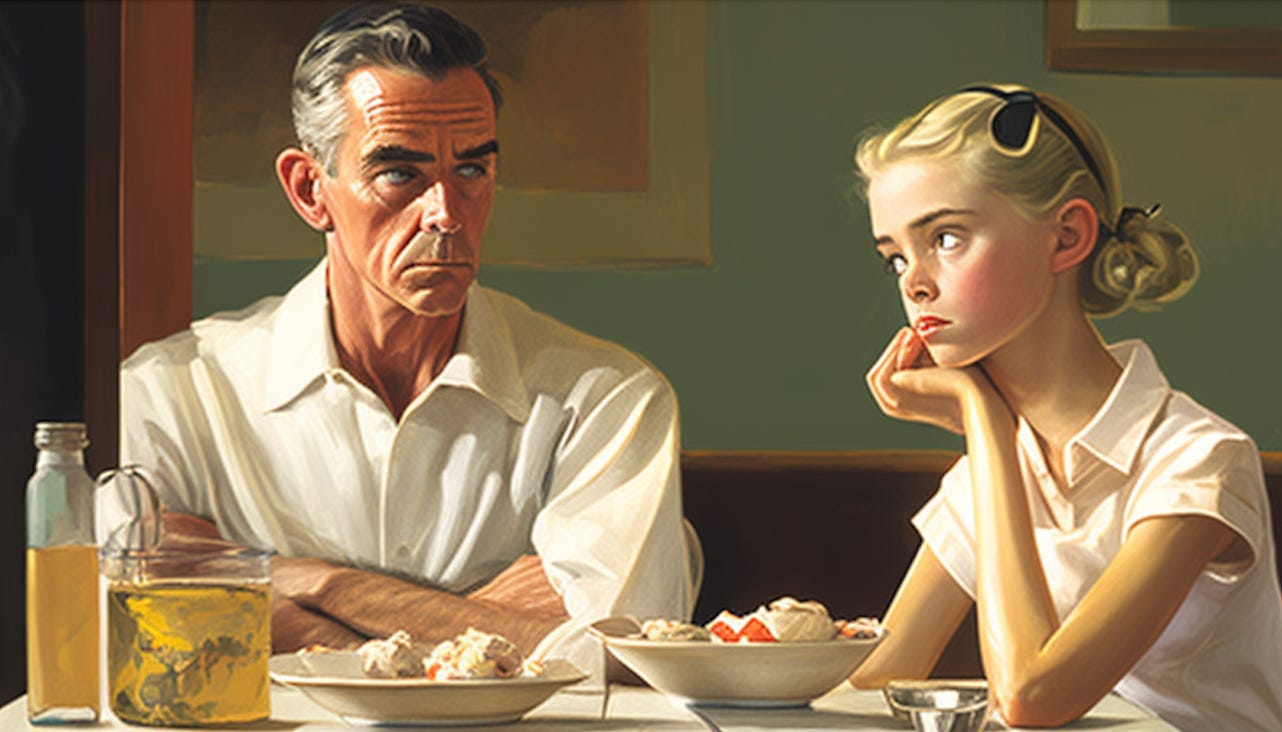

Here’s what we looked like to the outside: on one side of the table, you see an older man with dyed black hair, his expressionless face pointed vaguely upward, looking at something in the far distance while his hands, thin and clean, folded and refolded the paper case from his chopsticks. Across from him, there’s a teenage girl with weak, skinny limbs, and long, thin hair. She’s been crying, or maybe she’s about to cry. Maybe she looks angry, or maybe she seems scared. It’s unhappy though, you can tell. Of course you can tell.

There are many such dinners like this, post-divorce meals where a parent sits across from their child. Before my parents separated, back when I was a kid, we sometimes went out to dinner as a family of six. Four kids, two parents, mainly happy but sometimes harried. After my parents separated, I didn’t really see my siblings with my father. I’m the second-born, and perhaps the most trouble. And so my father chose to see me alone. Once a month, for around 90 minutes, we “visited.” This was almost always at a restaurant—rarely did I darken the doorway of his newer, larger, fancier home—and usually, we got sushi.

Sushi was my choice but I chose it for him, too. At the time, I was the only one of his six children—a number that then included my step siblings from the second of his four marriages—who enjoyed sushi. My father had served in the Navy, aboard nuclear submarines during the Cold War, always to classified places, and while traveling abroad he cultivated a taste for seafood. He liked salty sea urchins and rubbery octopus, foods that my mother (who has still never left the country) didn’t appreciate. Desperate to prove myself braver, bolder, and more urbane than the staid residents of suburban Massachusetts, I decided to like sushi, too. I was neither his smartest kid nor the nicest. I wasn’t the most useful or the most compliable. I decided to be the most adventurous—in eating, in travel, in love. Even in questions.

There are so many things he couldn’t tell me, or wouldn’t. But I asked anyway: Did you ever think you were going to die? (Yes. During the drills.) What was your favorite place? (Scotland, no real reason why.) Do you think there will be nuclear war in our lifetime? (It doesn’t matter, but probably not.) Do you think I’d survive? (No, no one would.) What was the worst part of living underwater? (Blanket parties.) Did you participate? (No comment.) How’s your sushi? (Good, try the Redsox Maki, see, this is called tobiko, the red fish is tuna…)

Sometimes, we’d trade roles. He would ask me short, quick questions, to which I gave long, meandering answers, chattering to fill the silence. I told him about my good grades, my excitement about college, my interest in traveling someday, not on a submarine, but I pretended briefly that maybe I would work a job like his, someday, despite not being at all cut out for military life. This didn’t make him like me any better, judging by how often we talk now. But for a time, we did see each other semi-regularly for dinner. Although the meals were wildly stressful—I couldn’t forgive him for cheating on my mom, especially with such a younger, smaller, and more educated woman – a “work colleague, and he couldn’t forgive me for being just so much my mother’s child—I still think of the restaurants fondly. They were the kind of medium-good restaurant that opens in wealthy suburbs of major cities (in our case Boston) around the country. My favorite was The Sushi House, located just down the road from the Concord Prison on a small, busy stretch of Route 2. It was easy to get to, not terribly popular, and perhaps a bit overpriced.

The Sushi House had everything you’d expect from an early 2000s Japanese-American joint. There were heavily used tatami mats covered with clear plastic runners (to protect them from Massachusetts slush), blond wood tables thickly varnished and slightly tacky to the touch, black mass-produced ceramics with unconvincing “brushstrokes” of red to create a faux-handmade finish, and several cat figurines, each waving a paw from a different window ledge or countertop. The sushi, however, was great. Or I remember it being great, though who knows what I would think now. At first, I remember ordering Philadelphia rolls and caterpillar rolls exclusively, two choices that contained no raw fish. I had been told that was dangerous, likely to lead to food poisoning. But my dad told me that was bullshit, that sushi was safer than lunchmeat, which meant soon I was trying all the dishes he ate—the spicy tuna, the baby octopus, the sea urchin, the fat balls of roe. It made me feel sophisticated and worldly, to eat these things, like I was on the edge of some new food trend, though inevitably by the time something made it to the quiet Boston suburbs, it was old news.

I still have no idea if I’ve ever eaten “authentic” sushi. I have yet to visit Japan, and I have my doubts about the very idea of “authentic” cuisine anyway. I loved the Sushi House for what it was—relatively private, quiet, and calm. I liked that I could eat something I enjoyed, and I thought I was showing my father I appreciated his likes and dislikes, too. Unlike my mother, I would eat raw fish. Unlike my siblings, I wanted to hear about his time serving in the Navy. I thought I was differentiating myself and that maybe he’d come to see me as separate from the rest of our family, my own person. One he could admire, because I admired him. My father had a PhD; he’d traveled around the globe; he worked a job that required government clearance.

And yet, even as I tried to ape him, I resented him. And that undoubtedly showed during our dinners. Only once were we mistaken for a couple, though that’s something that happens in movies all the time. Mostly, our waiters seemed to know exactly what we were. Two unhappy people trying to maintain peace, to use the tools of the restaurant business as props in our family drama. We were acting the part of two people who were interested in talking to each other, of moving forwards towards something better. I don’t know why that never happened. In all honesty, it was probably already too late. Maybe the resentment was already in my body. Maybe it had become a part of me on some deeper level, maybe it drifted out of my oily teenage pores, maybe it wafted off me, poisoning his meal. Maybe that’s why the platters of fish didn’t solve our problems. Maybe that’s why even an anodyne, neutral ground felt unbearably tense and maybe that’s why he could never seem to look me in the face. I don’t think he even noticed how I ordered what he did, how I followed his lead.

None of it mattered in the end. When I was 18, we stopped going out for sushi. “I think you purposefully choose the most expensive restaurants,” he said to me once. “Just like your mother.”

Katy Kelleher is a Maine-based writer whose work appears in Eater, Jezebel, The New York Times Magazine, and The Paris Review. Her essay collection The Ugly History of Beautiful Things is forthcoming from Simon & Schuster. Follow Katy on Twitter.

oh wow. the memories this opened for me. Choosing the duck to seem adult when dad took me out during his visits in college. Picking at my hash browns the next morning at the diner, because i was so hungover, partly from the wine at dinner but more so from the good old fashioned college binge drinking with an overlay of using-booze-to-stuff-your-emotions-down-deeper ... my sunglasses on the whole car ride... So many unspoken questions. I wish I could remember when I went from desperately seeking his approval to entirely faking interest in him and just waiting him out for the inheritance... feels like that would be an important moment to remember? if it was a moment, and not some kind of turning of the tide kind of intangible, immeasurable thing....