The Future of Restaurant Interior Design

If airspace, that defining contemporary urban design movement, is finally on the way out, how will Gen-Z’s chaotic aesthetic inspire the restaurant interiors of the future?

Different layers of the trend ecosystem move at different speeds. Fashion moves quickly, minute-to-minute and season-to-season. But interior design (and stuff that needs to be physically built out) moves a bit slower. And more and more of the aesthetics that dominated the interiors of coffee shops, co-working spaces, dwellings, and even restaurants for the past decade or so are looking played. I’m curious to see what the next wave of interior trends, driven by younger, hyper connected audiences will look like, and how they will vary from the DWR hangover miring much of contemporary design.

In 2016 the writer Kyle Chayka famously coined the term “airspace” to define this exact homogenous aesthetic that grew pervasive worldwide. It’s hard to put your finger on the exact parameters of it, but it's equal parts Brooklyn, a bit of watered-down Monocle, and a digitally-driven homogenization of aesthetics.

Then, there is the idea that in a world of Pinterest and IG explore pages, the same sort of references get played back to you rinse repeat, over and over.

Everything feels safe, not pushing any boundaries, but perfectly calm and comforting to sit in, clicking away at an Apple laptop while drinking some Rwandan coffee. Instagram played a huge role in the virus, allowing aesthetics to cross-pollinate quickly, but so did the rise of an increasingly mobile creative class, bopping between Berlin, Tbilisi, and Silver Lake. The aggregated market demand for this aesthetic also built upon itself, leading it to be one of the prevalent styles when you’re searching for a design-centric Airbnb. A certain aesthetic conveyed a knowing wink, and commanded higher rates.

But it seems we’re growing tired of this slick globalized creative aesthetic. Or, to put it more bluntly–as the editors at N+1 did last winter in their semi viral essay, “Why Is Everything So Ugly?”–design now suffers from a "theoretical possibility of endless variety [that] manifests as lackluster sameness," resulting in bland, brightly-lit, IKEA-inspired restaurants "that look like the apps that control them."

So, who’s to blame for this design purgatory we currently live in? Us millennials, apparently, though the blame can supposedly be tempered by the lack of choice we've been given.

“Who asked for all of this? Numerous critics — self-hating and otherwise — have argued that the mallification of the American city is the fault of the same millennials for whom all the new construction was built, who couldn’t quite bear to abandon the creature comforts of home even as they reurbanized. The story goes that millennials lived, laughed, and loved their way into an unprecedentedly insipid environment, turning once-gritty cities into Instagram-friendly dispensaries of baroque ice cream cones that call back, madeleine-style, to the enfolding warmth of their suburban childhoods. But the contemporary built environment is not the millennials’ legacy; it is their inheritance. They didn’t ask for cardboard modernism — they simply capitulate to its infantilizing aesthetic paradigm because there is no alternative.” — N+1

Whatever the case, it’s hard to isolate all of the elements that have contributed to design homogeneity, not just within interior spaces and coffee shops, but also in broader topics like graphic design, direct-to-consumer brands, and even personal aesthetics and style.

The top-line ingredients that go into this design stew are risk aversion, knowing what is resonating in the market, and not wanting to be bold to articulate a different design language. In a post about visual homogeneity, Alex Murrell in the Age of Average, suggests also that focus groups and market testing play a big role, in addition to the role of economics and material costs. If reclaimed wood tables and a certain type of lighting fixture are in vogue, then the price goes down considerably.

Then, there is the idea that in a world of Pinterest and IG explore pages, the same sort of references get played back to you rinse repeat, over and over. According to Elizabeth Goodspeed in an AIGA post, “the vast availability of reference imagery has, perhaps counterintuitively, led to narrower thinking and shallower visual ideation.”

So…where are we headed? And…where will we eat?

While a design revolution hasn’t swept restaurants yet–yes, the Edison bulb-illuminated eateries pioneered by Public before proliferating across Brooklyn last decade have mostly been retired to the Hudson Valley, but midcentury modern still abounds–we are starting to see an aesthetic response to this homogeneity in brands and culture. Burberry recently ditched their “blanding” for something more maximal. Brands like Flamingo Estate are building layered botanical worlds of luxury, not unlike what you would expect out of Hermès. And while big fit menswear still dominates the sidewalks of Nolita and the pages of GQ, there are rumblings that things like the recently derided skinny jean might already be poised for a renaissance.

But what does this portend for the future of interior spaces, especially restaurants, in a world where Gen Z opts for a more raw, iterative aesthetic and not the detached, minimalism with patches of warmth beloved by elder millennials? It’s hard to say what will win out, but one can extrapolate outward based on what we know seems important: An emphasis on sustainability and environmentalism could point to a more biophilic design — a design mimicking nature, with the integration of plants and other living elements into interiors. Then there are some of the future-facing innovations that we are in the first innings of: think 3-D printing, mushroom or lab-grown leather, and other new and novel materials.

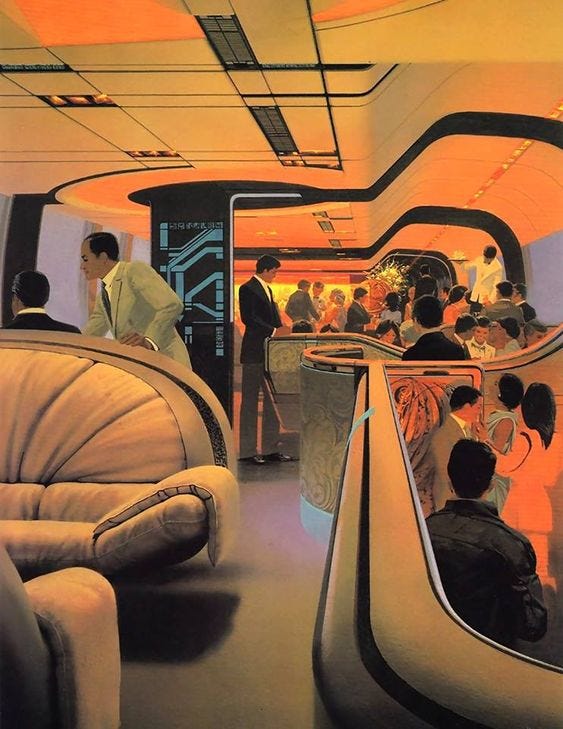

The Pinterest and IG explore page mood boards might be replaced by generative AI, eliminating the shallow visual ideation and allowing for a wider range of expansive thinking when it comes to potential art direction and references, pulling upon a wider range of ingested intellectual property and design history and spitting out things that are more warped and hallucinatory. For further evidence see everything from the epically baroque dreamscapes to the noir-inspired retro renderings cooked up on Midjourney.

If we observe other design trends, strong context is important for a space, and real estate is growing more expensive in urban centers: so imagine an interior of a restaurant that physically changes through the context of the day: a morning coffee shop, a co-working space, and then a wine bar with furniture that adjusts and morphs throughout. Perhaps we will see the automated physical flexibility that Ori Living does for converting small spaces, into restaurant and coffee shop interiors.

There’s also just the desire to buck convention, which we are actually starting to see the first rumblings of in restaurants. Casino, the latest Lower East Side eatery to capture the moment, feels like a pleasant zag away from the Brooklyn maker aesthetic. It feels vaguely Mediterranean, with a soft-washed interior that is an unlikely, acid trip pairing of Mykonos and Kubrick (and feels like a step in the right direction). J.Crew—a brand keen to shed the Mad Men coattails it rode and subsequently wore-out last decade—recently shot recipe developer Pierce Abernathy in one of Casino’s lipstick red banquettes. This felt like an appropriate pairing considering J.Crew’s unfussy approach to its particular version of affordable quiet luxury. Sure, Casino hums with a certain glamour, but it’s also pretty bare bones — economically inhabiting the former Mission Chinese space, with design, or at the very least aesthetics, being almost an afterthought.

That’s not to say that design is dead in the dining world. A few blocks south of Casino, and catty-corner from one another in Dimes Square, sit Le Dive and the Lobby Bar at Nine Orchard. Both are prime examples of fully realized aesthetic spaces, each over the top in its own way — the physical manifestations of hospitality professionals betting big on the Roaring Twenties revival that we were promised during the height of the pandemic. Restaurants, it would seem, are a reflection of the hodgepodge style we currently see on the downtown streets of NYC and elsewhere, a mix of Balenciaga and Hoka and Aimé Leon Dore and the latest hypebeast Samba collabs; an almost post aesthetic world where ostensibly anything—as long as it’s considered and calibrated—goes.

Regardless of the technology and trends, or the fact that a unifying design aesthetic for this decade and beyond has yet to emerge (and isn’t that a good thing considering the homogeny we’ve faced?), it is clear that the future interiors and hospitality spaces will be a reflection of Gen Z’s media consumption, social platforms, and accelerated digital connection, just as it was with Airspace 1.0. But the result will be less predictable and hopefully much more creative: we’re going to have to live with it for a while.

Colin James Nagy writes regularly on travel and culture. He is a regular columnist for Skift and co-founder of Why is this interesting, one of our favorite newsletters. He has written for publications including Monocle, Courier, AdAge, and New York Mag. Follow him on Twitter @CJN.

This reminds me of David Perell's writing about minimalism: https://perell.com/essay/after-minimalism/

It seems there's a regression to the mean when it comes to interior design, not only of our cafe and restaurant spaces, but also Airbnbs. The mean is seen as this "basic, most likely to cause bookings" kind of design. Problem is it lacks charm and personality. When we put those two things back in, we cater less to the masses and more to specific cohorts of customers. That might change the outlook on loyalty as well.